[ad_1]

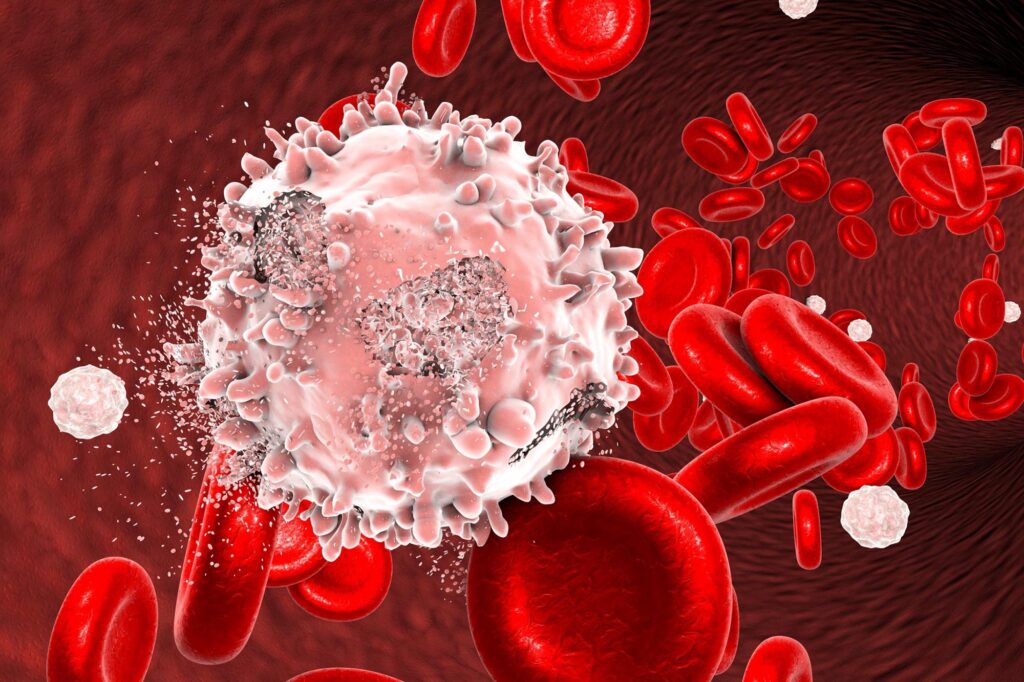

T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia is an aggressive and rapidly progressive form of leukemia.

Everyone has a small number of unusual thymocyte cells, and in some cases these cells develop into leukemia.

Researchers have discovered that T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL), which affects more than 6,000 Americans each year, can be caused by a dysfunction involving a specific type of thymocyte that is common in every human being tiny number is present.

Studying mice with T-ALL, scientists at the University of Missouri School of Medicine and College of Engineering characterized the thymocyte cells, an immune cell found in the thymus. They discovered that the same type of T cell, which produces a unique set of molecular markers, is the source of all rodent tumors.

“Once we identified the cell in mice, we wondered if humans had the same cell type and abundance,” said senior author Adam Schrum, Ph.D., associate professor of bioengineering, molecular microbiology and immunology, and surgery. “The human samples we obtained contained the same T cells and at the exact levels found in mice.”

This rare cell, which accounts for only 0.01% of all cells in the thymus gland, became known as “EADN”. Next, Schrum’s team wanted to know if every human T-ALL case came from EADN.

“Over a three-year period, we studied five T-ALL cases at the University of Missouri Health Care,” Schrum said. “We looked at cell samples from each patient and found that one of those five cases appeared to be from an EADN cell. We’re not saying that EADN is the only cell that causes this type of cancer, but our results show that it’s responsible for some cases. This is a very exciting discovery.”

Schrum’s team found something else unique about EADN cells. A molecule called the major histocompatibility complex (MHC), which drives autoimmunity and other immune responses, signals EADN cells to turn into cancer in mice.

“It’s like an autoimmune reaction that causes EADN to turn into cancer,” Schrum said. “Many other cells in the thymus cannot do this. Now that we have determined the signals required for this transformation, this discovery could point to possible strategies to address it.”

Schrum said the next step is to determine how common human T-ALL cases are from EADN cells, in hopes of learning how to better personalize treatments for each person’s unique cancer case.

The NextGen Precision Health initiative underscores the promise of personalized healthcare and the impact of large-scale interdisciplinary collaboration, bringing together innovators from across the University of Missouri and the three other research universities in the UM system to achieve life-changing advances in precision health. It’s a collaborative effort to leverage Mizzou’s research strengths for a better future for the health of Missourians and beyond. The Roy Blunt NextGen Precision Health building at MU anchors the overall initiative and expands collaboration between researchers, clinicians and industry partners at the state-of-the-art research facility.

Reference: “Early expression of mature αβ TCR in CD4-CD8 T-cell progenitors enables MHC to drive the development of T-ALL-carrying NOTCH mutations” by Kimberly G. Laffey, Robert J. Stiles, Melissa J Ludescher, Tessa R Davis, Shariq S Khwaja, Richard J Bram, Peter J Wettstein, Venkataraman Ramachandran, Christopher A Parks, Edwin E Reyes, Alejandro Ferrer, Jenna M Canfield, Cory E Johnson, Richard D. Hammer, Diana Gil and Adam G. Schrum, June 29, 2022, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2118529119

The authors disclose no conflicts of interest.

[ad_2]

Source link